Coastal blue carbon in a nutshell

A simple definition of blue carbon to start with

Blue carbon is a term that is used to describe the carbon sequestered and stored by coastal and marine ecosystems from the atmosphere.

Blue carbon is defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as ‘biologically driven carbon fluxes and storage in marine systems that are amenable to management’. ‘Blue’ refers to the watery nature of the carbon storage, recognizing that carbon dioxide dissolved in the ocean makes up the majority of blue carbon.

DIVE DEEPER

What is the difference between a blue carbon pool and a carbon sink?

A “blue carbon pool” is a reservoir where blue carbon is stored. A “carbon sink” is a process or mechanism that absorbs more carbon from the atmosphere than it releases (Scott and Lindsey 2022).

What is coastal blue carbon?

Coastal blue carbon is the carbon captured and sequestered by photosynthetic organisms and ultimately stored in the biomass, soils, and sediments within and beyond coastal vegetated ecosystems, for time scales relevant to climate change mitigation.

The three main blue carbon ecosystems

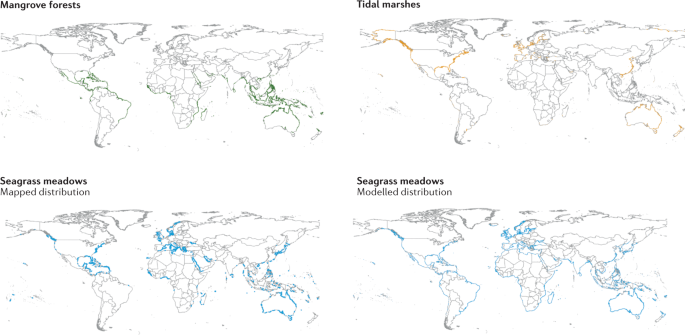

The three main blue carbon ecosystems are mangrove, seagrass and saltmarsh.

Their photoautotrophic systems have the ability to store carbon in their biomass or soil/sediment for relatively long periods of time.

All three ecosystems exist in tropical and sub-tropical ecosystems, but only saltmarsh and seagrass systems are common in temperate and northern regions (although recent research is indicating that temperate tidal swamps may function as important blue carbon ecosystems) (Brophy et al. 2011).

It is important to note that knowledge is very heterogeneous between the three blue carbon ecosystems. Indeed, mangroves are studied relatively better than seagrasses and salt marshes, i.e. they are studied by a larger community and are the subject of more scientific publications

How much carbon do blue carbon ecosystems stock?

It has been estimated that the global distribution of blue carbon in saltmarsh, mangrove and seagrass ecosystems range from ~36 to 185 million ha, potentially storing ~8,970 to 32,650 teragrams of carbon (Tg C) (Macreadie et al. 2021).

Beyond the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) mitigation potential of these ecosystems, Macreadie et al. estimated in 2021 that protecting existing blue carbon ecosystems could avoid emissions of 304 (141–466) Tg (95% CI bounds) carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) per year.

This range reflects the uncertainty of global mapping initiatives, carbon stock estimates, and carbon sequestration rates in blue carbon ecosystems, especially in northern and remote areas where in situ measurement and mapping of Blue Carbon Ecosystems (BCEs) is coarse or poorly understood.

Why are blue carbon ecosystems important?

Blue carbon ecosystems can mitigate global warming

The IPCC pointed out in 2022 that coastal blue carbon is concentrated in rooted vegetation in the coastal zone, and also notes that these blue carbon ecosystems’ have high carbon burial rates per unit area basis and accumulate carbon in their deep and water-logged soils and sediments’. This is why, despite its relatively small global footprint, BCE’s contribution to global biogeochemical cycles is now at the forefront of global warming mitigation.

Regional carbon budgets need to be assessed to gain a deeper insight into the flow of organic and inorganic carbon on a global scale, in order to contribute to the goals of the Paris Agreement and the Global Stocktake agreed at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP28).

Blue carbon ecosystems are powerful nature-based solutions

In addition, BCE are increasingly being presented as cost-effective nature-based solutions (Macreadie et al. 2021) due to the multiple services they provide for the conservation of coastal biodiversity, human well-being, protection against severe storms and carbon storage in view of developing sustainable blue economy (O’Leary et al. 2023).

Blue carbon ecosystems can fund their own conservation and restoration

As with terrestrial forests, new policy initiatives and projects to conserve, restore and enhance blue carbon stocks are being put on the table with a view to trading the carbon storage capacity of BCE in carbon markets.

It is therefore crucial to monitor BCE accurately in order to assess the carbon balance resulting from disturbances induced by a wide range of drivers (climate change, human activities, natural processes) or restoration and protection management plans.

Overall, blue carbon ecosystems should not be regarded as uniform carpets of biomass, easily accountable and easily manageable. They are complex lived-in carbon landscapes and cannot be resumed in numbers, measurement, models and management processes cemented by the only carbon approach alone.

Rigorous remote sensing approaches can be beneficial for all scientific disciplines involved in BCE monitoring, including new insights into the complex functioning of the blue carbon coasts.